|

"Man. Probably the most mysterious species on our "Man. Probably the most mysterious species on our

planet. A mystery of unanswered questions.

Who planet. A mystery of unanswered questions.

Who

are

we? Where do we come from? Where are we are

we? Where do we come from? Where are we

going? [. . .] Countless questions

in search of an going? [. . .] Countless questions

in search of an

answer... an answer that will give rise to the next answer... an answer that will give rise to the next

question... and the next answer will

give rise to the question... and the next answer will

give rise to the

next question, and so on. But, in the end, isn’t it next question, and so on. But, in the end, isn’t it

always the same question?" always the same question?"

Policeman in Run Lola Run. Policeman in Run Lola Run.

Have you ever had the impression of being in front of a web

page when watching a movie? Have you ever found yourself trapped

in a labyrinth of multiple simultaneous options? If not, watch

Run Lola Run (1999) by Tom Tykwer, which is basically

a celebration of the simultaneity of possibilities and the

total annihilation of any original possibility. At a single

glance, this may appear to be a frankly postmodern work due

to its wide unfolding of greatly varied possibilities, reminiscent

of the seemingly infinite avenues and resources of the internet.

At the same time, it evokes a highly chaotic environment,

as the multiplicity of possible pathways would appear to present

no clear order or direction. However, a deeper analysis of

the wide range of possibilities in both the movie and the

internet does reveal, as the linguistic and anthropological

structuralism of Saussure and LÚvi-Strauss suggest, respectively,

that all these options are in fact subordinated to a deep

structure governed by difference. In both Run Lola Run

and the worldwide web this structure is exemplified in the

binary opposition of information providing instant gratification

versus information which come neither fast nor gratifying

enough.

| In his Course in General Linguistics (1916)

Saussure makes clear that language is a system of interrelated

signs and that, apart from the diachronic studies of

language, "the scope of linguistics should be: [. .

.] to determine the forces that are permanently and

universally at work in all languages, and to deduce

the general laws to which all specific historical phenomena

can be reduced" (6). On the other hand, LÚvi-Strauss

states in "The Structural Study of Myth" (1951) that

"[. . .] human societies merely express, through their

mythology, fundamental feelings common to the whole

of mankind, [. . .]" (207). It is the "spirit of the

nation" (Volksgeist) that Hegel had already formulated

in The Phenomenology of Mind (1807). It is along

these lines that I am organizing my reflections on Run

Lola Run and the internet with the object of explaining

the "general law" "common to the whole (of) mankind"

that governs our "dot com" civilization. |

|

Briefly, the synopsis of Run Lola Run is as follows:

Lola receives a phone call from her boyfriend Manni at 11:40

am, who tells her that he is in trouble and needs 100,000

Deutsche marks before 12:00 pm, or he will probably die. Lola

has only twenty minutes to come up with the money, and in

the first moment following the phone call her mind flashes

through various possibilities. She tries several of these

possibilities -- three in particular -- through a series of

flashbacks and retries until she finds the possibility (or

link) that finally offers her the most gratifying solution.

As Sam Adams points out in his review of Run Lola Run,

"she does not quite make it the first time, and when she fails,

the film resets itself and Lola is back at the beginning,

getting Manni’s fateful phone call all over again. She

tries again, she fails again. On to round three" (1).

These different links or possibilities correspond with what

Mark Poster, in his article "Postmodern Virtualities", calls

"virtual realities", which are no more than "computer-generated

‘place(s)’ [. . .] viewed by the participant through

‘goggles’ [. . .]" (616). In fact, Lola sees these

"virtual realities" through the ‘goggles’ of her

imagination while agonizing on the floor following her pursuit

of the first failed possibility. Indeed, using a device which

evokes a striking similarity to "computer-generated places",

Tom Tykwer often depicts Lola as an animation in a cartoon

world, running through different tunnels and environments

encountering (and often destroying or avoiding) potential

obstacles that would rob her of precious time. These scenes

reminiscent of "virtual realities" set the stage for each

alternative possibility that Lola pursues.

It is in this sense that Run Lola Run is an allegory

of the deep structure of the internet. Like the multiplicity

of hyperlinks in the web, the movie by Tom Tykwer unfolds

a multiplicity of options to follow, with three possible scenarios

each being followed to a different conclusion. At the same

time, we are given a glimpse of how each of these scenarios

impacts the lives of secondary, largely incidental characters

in the movie, evoking similarity to the many sublinks encountered

while navigating the internet. On this device, Sam Adams comments

that "not only does the film shift into animation at regular

intervals, but the story spins off at tangents, using a series

of rapid-fire snapshots to show the future history of characters

Lola passes on her journey" (19)1. Clearly it is

not just the World Wide Web which, as Mark Poster puts it,

"allows [. . .] simultaneous transmission of text, images

and sound, providing hypertext links as well" (621).

Both in the web and in Run Lola Run everything seems

to be a chaos of possibilities with little apparent organization.

In the first possible ending of the movie Lola lays dying,

whereas in the second scenario it is instead her boyfriend

Manni. Lola would, of course, prefer neither of these outcomes,

and utters the word "stop!" moments before her own death in

the first round, which resets the movie to the opening scene,

allowing an exploration of other possibilities. In the second

scenario Manni is the one who lays dying as he states a clear

"no", causing the movie to again revert and allowing the third

possible link or ending, in which neither of them dies. These

responses of Lola and Manni may appear as acts of autonomous

human beings reacting to a situation according to their own

will. However, in truth the only real ending of the movie

was the first one. The rest are a product of Lola’s

imagination, representing what could have been had other paths

been followed, and Lola, always running, is just a puppet

of the basic structure to which she is subordinated: is the

information that this possibility provides fast and gratifying

enough?

This is the structure governing the system. Thus, as Tom

Tykwer offers multiple endings, all of which are possible

if not real, to Run Lola Run, the clock serves as a

constant reminder that Lola has only twenty minutes to get

the 100,000 marks. In that twenty minutes the third path would

have resulted in the most satisfactory and efficient ending

of the movie according to the present cybernetic culture:

it has a happy ending, with Manni successfully resolving his

problem on his own, and Lola acquiring the money anyway. This

begs the question: what of the many other possibilities or

links that could have been pursued in the movie? What other

information would they have provided us? Tom Tykwer offers

the answers to these questions for only three of the possible

scenarios with his digressive snapshots summarizing the future

lives of several secondary characters in the movie. In truth,

the insight provided by such digression is irrelevant in cybernetic

culture. Once a satisfactory outcome or the desired goal is

achieved, no more exploration is necessary; other information

not ultimately a part of the most gratifying and efficient

pathway is disregarded.

In this sense, Run Lola Run is like a web page full

of links. The main character, Lola, chooses the "links" she

supposes to be the most efficient and likely to achieve her

purpose of finding the 100,000 marks. When she does not like

the ending that her selections have taken her to, she backs

up and makes another choice, following another "link", just

as we do while navigating the internet. If Saussure defined

language as a system of signs governed by difference, Run

Lola Run is the system, whereas Lola’s different

options are the signs characterized by a binary code composed

of that information which is timely and gratifying enough

opposed to that information which is not. Applying Saussure’s

theory to the web, we see the internet as a system and the

web pages as the signs, which fulfill the following main functions:

1) self-publishing; 2) research; 3) communicating with others

(most significantly via chatting and email).

Critics such as Mark Handley and Jon Crowcroft in The

World Wide Web define the internet as "[. . .] a great

tangled web of information" (31). Daniel Barrett states in

Net Research: Finding Information Online that "the

Internet is a jumble of facts, opinions, stories, conversations,

arguments, artwork, mistakes, trivia, and one-of-a-kind knowledge.There’s

little organization or consistency" (1). Moreover, he adds

that "the internet isn’t conveniently organized. It’s

too big, and it’s constantly being modified by thousands

of people who don’t know each other" (23). While this

latter assertion is correct, in truth there exists a deep

structure which drives these three functions of the web, despite

the appearance of little organization that these and other

critics find in the internet. This structure is evident as

a network of instant, gratifying information which, in the

case of function 1) and function 3), is reduced on many occasions

to the structure of what I call fast love. To this regard

Mark Poster quotes Howard Rheingold, who states "[. . .] I

and thousands of other cybernauts know that what we are looking

for [. . .] is not just information but instant access to

ongoing relationships with a large number of other people"

(qtd. in Poster 619). A deeper analysis of each of these three

functions reveals these points more clearly:

The first function, self-publishing, responds to the need

of presenting critical or personal (as is often the case with

personal web pages) information in a rapid manner. In both

cases, the publisher looks for recognition or fast love from

the cybernaut who receives the information. On the one hand,

creators of web pages with critical information look for,

at the least, acknowledgement and validation (whether or not

the viewer agrees with the ideas presented), and thus these

web pages distill to nothing more than the basic imperative

"look at me", the naive question "am I good enough?" or, more

simply, the plaintive "do you love me"? On the other hand,

personal web pages contain a great amount of false information,

since in the majority of cases the main motive of the page’s

creator is not truth per se but rather the desire to present

him- or herself in a likeable way, regardless of reality and

perhaps at the expense of frank honesty. Clearly truth is

not the basic structure governing the web system. Rather,

instantly gratifying information and fast love are2.

The second function, research, belongs solely to the structure

of instantly gratifying information. There are millions of

web resources within our immediate reach. The problem is,

according to Daniel Barrett, that there is no clear organization

or structure to the internet, and thus finding information

online might not always be an easy task. The author compares

the internet with "[. . .] a huge collection of libraries

scattered around the world", each of them with "[. . .] its

own method for organizing and accessing information" (30).

Furthermore, "there’s no roadmap to get from one library

to another" (30). Barrett continues on to discuss how "an

organized view like Yahoo’s imposes order on the chaos

and provides a structure for your search. But it’s not

the structure" (23). It is true that Yahoo, as with

many other web pages, imposes an interface that in reality

is not the structure of the internet. But this does not mean

that no structure exists. The structure of the internet is

not a superficial one, but rather is a deep structure not

explicitly displayable through dashes, sections, and letters

as pages such as Yahoo might provide. It is a structure based

upon gratifying information provided rapidly.

The third function of communicating with others via the internet

(mainly through email and chatting) is, like the first function,

a link in the structure of both instantly gratifying information

and fast love. When we send an email to a friend, a professor,

a business person, a librarian, etc., we normally do so because

we want to transmit and receive information as quickly and

conveniently as possible. In the case of chatting, particularly

in the "singles" chat rooms, there are the additional aspects

pertaining to the structure of fast love. For example, questions

such as "a/s/l?" ( = age? sex? location?) are prevalent in

chat rooms, which ask for personal information in a very immediate

fashion, using only a few letters in the place of full words.

Furthermore, if the answer to the question is not satisfactory,

he or she does not even have to bother answering. The web

confers an anonymity that allows the principles of politeness

to be ignored and societal formalities to be dispensed with

for the sake of instant gratification. If the chat inquirer

has not found information that is satisfactory or pleasing,

he or she may simply move on to a different person with the

same question: a/s/l? Each respondent does likewise: after

presenting him- or herself to the initial inquirer and receiving

no follow-up conversation, he or she moves on to the next

person without giving it further thought. This is a perfect

example of what I call searching for instantly gratifying

information or fast love.

These three functions with their multiplicity of links can,

at a single glance, give the impression of the web as a growing

monster with infinite heads. However, this monster of the

web and its signs are governed by a structure. It is a deep

binary structure such as the one evident in Saussure’s

linguistics or in LÚvi-Strauss’ anthropological studies,

a structure that contains signs defined by their opposition

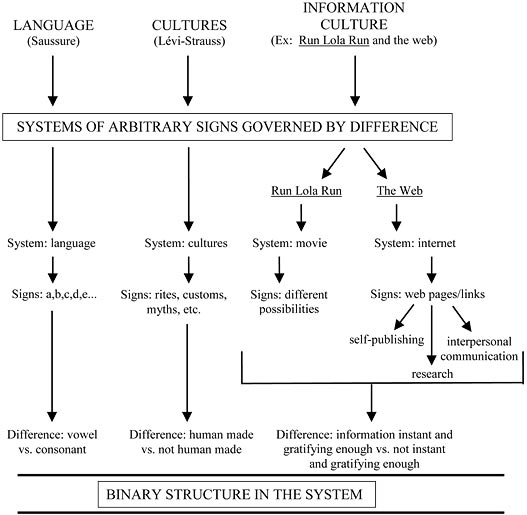

within the system3. The following comparative chart

illustrates this:

This chart illustrates the fact that the information culture,

just as the linguistic and cultural systems of Saussure and

LÚvi-Strauss is governed by a binary structure formed by pairs

defined by difference. Saussure focused on the language system,

and LÚvi-Strauss focused on the study of different cultures,

particularly on their myths. Influenced by Saussure, LÚvi-Strauss

asserts (as reported by Mary Klages in "Claude LÚvi-Strauss:

The Structural Study of Myth") that "[. . .] myth is language,

because myth has to be told in order to exist" (1). However,

the emphasis placed on the visual in the present information

culture obscures the fact that it is actually language that

is the operative system, just as Saussure and LÚvi-Strauss

have stated. Although language occupies a great part of the

movies and internet today, this system increasingly shares

its protagonism with the visual image due to the rapidity

and immediacy of the information conveyed. As instant gratification

is the operative structure nowadays, images have become more

and more attractive in the communication culture, while also

competing on many levels with and acting to undermine the

linguistic element of this culture.

Regardless of the system, be it exclusively linguistic or

not, the basic structure of the system is key in both Run

Lola Run and the internet. In Tom Tykwer’s movie,

Lola’s different options are interrelated as signs having

in common the same binary structure (information instant and

gratifying enough versus information not sufficiently rapid

and gratifying)4. In the same way, we see how in

the web the functions of self-publishing, research, and communicating

with others respond to the same binary structure. The third

function in particular comes at the cost of language in many

cases, due to the use of abbreviation slang, emoticons, and

different images (i.e. pictures) in chat rooms.

Thus, contrary to the anti-structuralist arguments of Handley,

Crowcroft, Barrett and others, the web (like Run Lola Run)

does present an organization that corresponds with a deep

structure. As Hans Bertens underscores in Literary Theory,

"[. . .] we are only dealing with variants upon what is essentially

an unchanging basic pattern" (64). In this sense, both Run

Lola Run and the web are networks of structuralist possibilities.

As the policeman states in the opening statement of the movie,

in the end, it is always "the same question", which in our

present world governed by technology is this: is the information

you provide instant and gratifying enough?

Notes

1 In her review of the movie, Karina Montgomery

relates these side stories to "the concept of ‘what

if’": "[. . .] this movie takes ‘what if’

to a new level [. . .] Run Lola Run [. . .] has the

bonus of having all kinds of interesting side stories –they

whisk by but still register- they are not important, they

are only secondary to Lola’s run" (1).

2 LÚvi-Strauss points out in "The Structural

Study of Myth" that truth is not the structure governing

humanity’s myths either. What is important are the

relationships established between the mythemes: "There is

no single ‘true’ version of which all the others

are but copies or distortions. Every version belongs to

the myth" (218).

3 See General Linguistics Course by Saussure,

and The Raw and the Cooked by LÚvi-Strauss.

4 In order to carry out the representation of

this search for instantly gratifying information, the director

of Run Lola Run makes imperative use of the image

in movement (ie, images of Lola constantly running) accompanied

by music with rapid rhythm, to the detriment of words. The

characters in the movie actually speak relatively little,

with much of the story being covered by the initial narration

and subsequent soundtrack. As Sam Adams puts it, "once Lola

has started her everlasting sprint, the music runs almost

without stopping for the next 70 minutes. Even when the

volume drops to allow us to hear the film’s few exchanges

of dialogue, an incessant tick-tick-tick keeps time underneath"

(1).

Works Cited

- Adams, Sam. "Run, Lola, Run". July 1-8, 1999. Philadelphia

Citypapernet. January 2003. <www.citypaper.net/movies/r/runlolarun.shtml>

- Hegel, George. The Phenomenology of Mind. Trans.

James Baillie, New York: Harper & Row, 1967.

- Barrett, Daniel. Net Research: Finding Information

Online. Sebastopol, CA: Songline Studios,

1997.

- Bertens, Hans. Literary Theory. New York: Routledge,

2001.

- Handley, Mark and Jon Crowcroft. The World Wide

Web.

London: UCL Press, 1995.

- Klages, Mary. "Clade LÚvi-Strauss: The Structural Study

of Myth". September 15, 1997. University of Colorado

at Boulder. January 2003.

<www.colorado.edu/English/ENGL2012Klages/levi-strauss.html>

- LÚvi-Strauss, Claude. "The Structural Study of Myth,"

Structural Anthropology.Trans. Claire Jacobson

and Brooke Grundfest. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

- ---. The Raw and the Cooked. Trans. John Weightman

and Doreen Weightman. New York: Harper and Row,

1969.

- Montgomery, Karina. "Run, Lola, Run (Lola Rennt) ". Cinerina.com.

June 18, 1999. Movie Reviews by Karina Montgomery.

January 2003. <http://www.cinerina.com/reviews/run-lola-run-lola-rennt/>

- Poster, Mark. "Postmodern Virtualities" Media and

Cultural Studies. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell,

2001.

- Run, Lola, Run. Dir. Tom Tykwer. Sony Pictures

Classics & Bavaria Film International. 1999.

- Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics.

Trans. Wade Baskin. London: Peter Owen, 1959.

Links to paper in PDF formats

PDF

|